Corporate social responsibility or social performance has evolved rapidly in recent years. What stage is your company and what do you do? Where would you like to go?

The concept of Corporate Social Responsibility has gradually been replaced by Social Performance. This change has to do not only with the name itself, but with the evolution of social practice in industry, especially in extractive industries. And if we go back to the antecedents of CSR, social management and social performance, the evolution has in fact generated important changes, and it goes without saying that it has gone down well with both companies and the local communities where industrial operations are located, as the evolution of the concept and practice has been closely related to the perception and the idea that companies have of these communities, and the position they give them in the processes of dialogue, negotiation, agreement and development management. And, obviously, this evolution has had everything to do with the perception and idea that local communities have of themselves, and the way they exercise their rights.

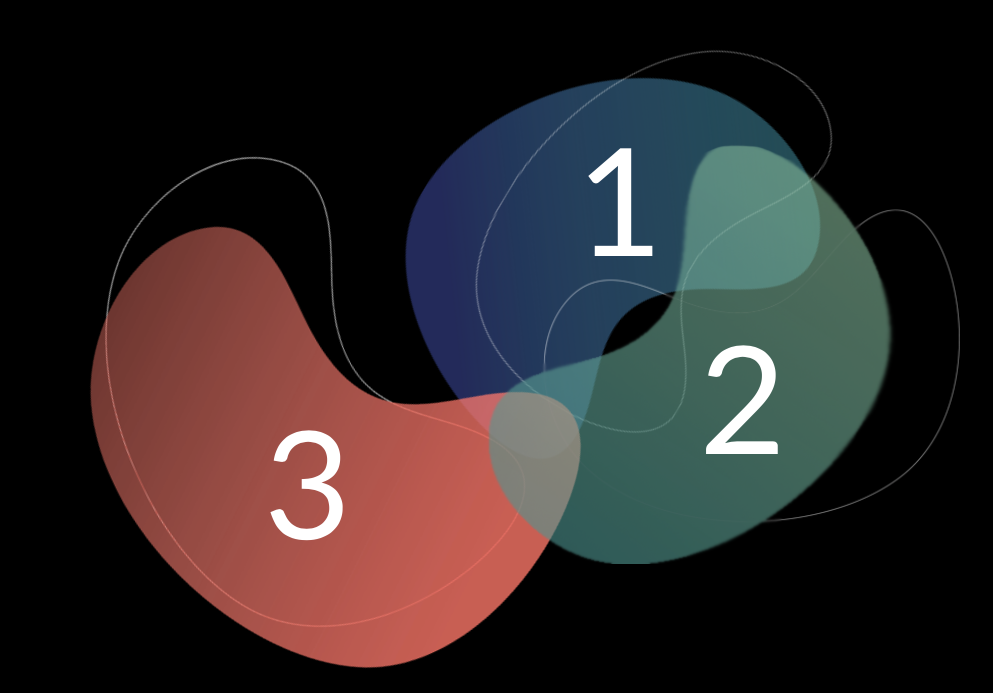

In this blog post we take a look at this evolution in 3, 2,1.

3.... The Philanthropy-based model:

In the earliest stage of corporate social responsibility, communities were perceived and understood in the third person as opposed to the first person, I, i.e. represented by the business. That third person was the other, he, she, they, and even that: a distant, chaotic, difficult to understand and contain, changing reality; in general, a group of people who live and make use of the territory where the sites are located and, therefore, not necessarily very beneficial to the objective of the business. Companies, honestly speaking, tended to put communities in a position of inferiority, so there was no room for conversation, either before or during the implementation of the business in any territory. However, this different and distant other is usually also in a situation of poverty, which motivated a philanthropic sentiment to help them overcome their situation of inferiority, supply their basic needs and, why not, facilitate the exit of this other from the area of influence of the projects to be able to operate them more easily.

Not to mention the type of philanthropy. A model based exclusively on what companies considered to be the needs of others, as well as donations or gifts to meet those needs in the immediate term. Little was known, at that time, about participatory, strategic, long-term planning or the idea of sustainable development, so everything was based on the goodwill of a manager with the best of intentions, and that was it.

I am convinced that we should not judge our past with the eyes of the present, those were different times for humanity. But I am so glad that we have moved beyond those times! This period of disconnection between the other (the communities) and the Self (the companies) was not only framed by philanthropy, but led to abuses, conflicts, displacement, loss of land and, obviously, failure of some businesses. This crisis situation initiated the movement towards a stage with more and better rules for relating to the other: we moved towards Two.

2... The standards stage:

In the last two decades (although it obviously started earlier) we have all become more and more aware that we are subjects of rights and we are incorporating the capacity to exercise them in all areas. This exercise leads to the recognition, on the part of the state and the private sector, that those others who before seemed strange, uncontained and chaotic, were really organised communities, groups of people and families exercising their freedoms, an idea that has evolved to place people and companies in a place of greater equality, but not of greater equity, but little by little companies are putting local communities in the second person, and the conversation is moving towards the you and you as opposed to the I, the first person of the business. In this position, the you and the you give a human character to the other, gives legitimacy to the other, and the I feels more confident in addressing the other.

The adverse results of the philanthropy approach led to the development of standards, policies, best practices and a set of rules of the game for the relationship between companies and communities, to demarcate the conversations in order to keep them on the rights court. These include initiatives such as the Voluntary Principles on Security and Human Rights; the Ruggie and UN principles on business and human rights; the International Council on Mining and Metals (ICMM) statements on mining and indigenous peoples, water management, transparency, protected areas, climate change, among others. Development agencies such as the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and other entities in the financial world such as the International Finance Corporation (IFC) with their performance standards and norms for environmental and social sustainability, which have established stricter social (and environmental) management rules for financing large projects and monitoring compliance, under penalty of sanctions or denial of loans in the future. There are countless initiatives to standardise social performance and frame it in recognition of and respect for human rights and the legal rights of the parties, so that there is a clearer reference for the relationship, conversations and negotiations between you (second person, the communities) and me (first person, the company).

In the current model of standards, the second person begins to emerge, a we emerges , the recognition that there is a common world between companies and communities over interests in the same territory, over the rights of communities over it and over their own determination, and over the legal right of companies to implement projects.

This approach has undoubtedly contributed to reducing abuses, conflicts and also the resistance of communities to the development of projects in their territory. It has also led to a greater awareness of the rights of people and communities, and how to create spaces for the exercise of these rights in the relationship with the company. Social performance is now a discipline with a growing position within organisations, with greater professionalisation and, increasingly, with greater participation in business decision-making, and the voices of communities now have a place in these decisions.

However (yes, there was indeed a but...), there are still high levels of dissatisfaction in the communities, and socio-environmental conflicts related to the development of the extractive industry do not cease, there are still companies that do not fully comply with the standards because they consider, in a rather unfounded fear, that these may affect the full exercise of the business and, therefore, their economic returns.

Both sides are right, there is truth in each position. The dissatisfaction of the communities largely comes from the fact that the high standardisation of the relationship leaves little room for the human, for a real meaningful conversation, for a dialogue of equals, for joint construction; furthermore, it has become the perfect justification for any impact, as long as it is within the established limits, even if it is close to the outer edge of the field, it is still valid. Communities continue to see how the presence of large operations in their regions continues to fail to deliver results for regional development, while poverty conditions remain (and worsen). People do not feel that they are being heard, and so the need to complain arises. -At the same time, companies see how the implementation of high standards has costs in time and resources (human and financial), but they do not necessarily see immediate results, discontent is not reduced, reputation does not always improve, and productivity remains the same. The question then arises, what is the point of standards?

Another major limitation of this approach is that it has been interpreted from a risk perspective towards the business, which has meant that standards have been used as "armour" (in business terms) for operations, or that it again brings the conversation back to the I vs. a regulated You, but with little room for the construction and exercise of the we.

And it goes without saying that even with high requirements from international organisations, there are companies that have decided not to align themselves with the standards and follow from a Three or even earlier perspective, where anything goes for business development.

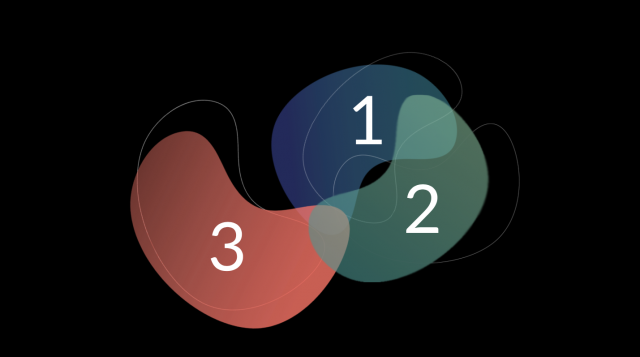

1.... The tuning perspective:

Society has evolved, the world has changed at a dizzying pace. Marches, protests and clamours from communities in entire countries have mobilised with one objective: to raise their voices, to be heard, to express their discontent with inequality, inequity and exclusion. Different sectors have the same claim. Regardless of the form the protest takes and how it assumes its place in different parts, at its core is a call for inclusion. Although there have been surges of movement and then lulls, it does not seem that the movement will completely cease until the reasons and causes of dissatisfaction and inclusion are honestly addressed.

In this context, standards are fundamental but insufficient. Me vs. you is even more frustrating for both parties. And it does not generate greater inclusiveness in sustainable development, nor does it facilitate the execution of industry projects and operations.

So, the time has come to create a space for the Wefor attunement, for connection within the framework of recognising the simplest element: humanity. The risk perspective towards business is not enough, just as it would not be enough to move to a purely social perspective (some reader will have heard that "this is not an NGO or a development agency"). In the We, the I (the company) recognises and acts according to its objective, to be a productive business; the communities, the You, are given room to assume and incorporate their rights and exercise them in decision making. In addition, the realities of the context are recognised, inequalities are highlighted, and the conversation revolves around co-constructing the idea and actions for comprehensive and inclusive sustainable development.

And we understand each party's place and role in catalysing regional development and integrating efforts to address and connect each other's objectives.

In We we legitimise the other in their place and their rights, create space for listening to all voices, for difference and conflict, and the movement and creativity it enables. To get to the We, it is essential to include, strengthen and sustain the previous stages, philanthropy and standards, and transcend into connection and attunement, to humanise our social practice.

Where is your company today, how do you tune in and be a catalyst for development? Our next blog will delve deeper into this topic. See you soon.